CLIENT NEWS: The end of Wynwood? Massive projects would remake Miami’s hippest neighborhood

June 25, 2024Miami’s Wynwood may be the hottest, hippest neighborhood in America’s hottest city: A dynamic urban fusion of repurposed industrial buildings and warehouses interspersed with new, low-rise buildings housing shops, bars and restaurants, offices and apartments, all of it steeped in artful design and curated graffiti murals.

Its success is no accident. The reinvigorated Wynwood, once a derelict industrial zone, is the deliberate result of unique planning guidelines and development limits painstakingly laid out a decade ago by district property owners and city of Miami planners. The special Wynwood regulations are backed by a distinct vision ‘ for a dense yet human-scaled alternative to the new high-rise forests of Brickell and Edgewater.

But just as they begin to bear fruit, the carefully laid plans for Wynwood are threatened by a controversial new state law, the Live Local Act, which overrides local building controls and encourages developers to supersize projects in exchange for setting aside apartments as ostensibly affordable housing. Critics say Live Local is a giveaway to developers and the promised affordable housing is anything but that.

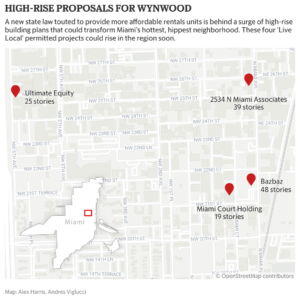

In Wynwood, Live Local looms in the form of a developer’s plan for a 48-story tower ‘ 36 stories taller than the highest building now allowed in the district ‘ atop a massive parking garage that by itself is larger than much of the new construction in the neighborhood. The Wynwood Neighborhood Revitalization District rules, by contrast, have restricted new buildings to 12 stories.

The tower plan, by Bazbaz Development, calls for 544 apartments and even more cars and parking, or 621 spots, at North Miami Avenue and Northwest 21st Street. That would effectively bring a downtown Miami density to narrow Wynwood streets already nearly overwhelmed with traffic and infrastructure that has barely kept up with the current wave of redevelopment.

And the tower project is only the first to surface publicly in Wynwood. City planning officials say five other Wynwood applications have been submitted this year.

Records provided to the Miami Herald by the city for three of the proposals call for:

- A 39-story tower with 336 apartments located four blocks north of the Bazbaz project, also on North Miami Avenue, by an affiliate of New York’s Hidrock Properties.

- A 19-story high-rise with 401 apartments located one block west of the Bazbaz site. As part of the project, Miami Court Holdings would preserve and protect an adjacent, two-story Art Deco building as part of the project.

- A 25-story building complex ‘ with 996 apartments and 693 parking spaces located along Northwest Sixth Avenue between 24th Street and 26th Street on the western edge of Wynwood along Interstate 95 ‘ is proposed by property owner David Sedaghati’s Ultimate Equity.

Local stakeholders expect more. They fear Live Local projects will turn the carefully nurtured district into another version of Edgewater, the nearby, rapidly changing, bayfront neighborhood that now consists mostly of towers rising from bulky, street-filling parking pedestals.

“If those controls are now overridden by Tallahassee, which has no idea what Wynwood or any neighborhood is, that’s kind of crazy,” said Juan Mullerat, a Miami planner whose firm, PlusUrbia, wrote the award-winning Wynwood plan, which was adopted as law by Miami city commissioners in 2015. “And it’s a little scary. Come Live Local, and you can just go nuts.”

QUESTIONABLE AFFORDABILITY

As to the promised affordable housing in the Bazbaz tower?

Though the specifics haven’t been decided yet, it’s likely to be around 217 apartments, mostly studios, aimed at people making up to 120% of the median household income in Miami-Dade County ‘ the level set by the state’s Live Local legislation. In 2024, under published calculations by the state, that means people making up to $95,400 a year can be charged up to $2,385 per month in rent for a studio. Rent for a one-bedroom would be capped at $2,554.

Live Local ‘ a priority of Florida Senate President Kathleen Passidomo, a Republican from Southwest Florida, and credited to Sen. Alexis Calatayud, a Republican from Miami-Dade County ‘ was billed as the answer to the state’s housing crisis when it was passed in 2023.

It unilaterally lifts zoning restrictions across the state for developers of mixed-use projects that set aside 40% of residential units as workforce housing for 30 years. Housing advocates say local zoning restrictions have often blocked development of affordable dwellings.

It also directs hundreds of millions of dollars in funding and tax breaks to developers who use the law’s provisions to build.

Live Local quickly proved controversial as developers began proposing outscaled projects in municipalities ranging from Doral to Hollywood and Miami Beach. The law’s pre-emption provisions apply in commercial, industrial and mixed-use areas.

In South Beach, the city of Miami Beach has tried to bat back a developer’s plan to replace much of the Clevelander Hotel on Ocean Drive in the Art Deco historic district with a tower.

Another proposal, by the owners of the Bal Harbour Shops, would put a hotel and residential towers atop the mall, which sits in a neighborhood where building heights are capped at three stories. The mall owners sued the village government when elected officials balked at approving the plan in the face of an outcry by residents who had previously voted to block expansion of the shops.

Glitches in the original Live Local language allowed municipal officials to block some of the proposals. But this year, state lawmakers approved revisions that were written largely by ‘ lawyers for developers and supercharged the law, rejecting objections from local officials who say it will allow developers to bulldoze neighborhoods with little to no consideration of urban planning or existing and historic character or scale.

At the same time, the Legislature barred local governments from imposing rent controls on private housing and made it harder for municipalities and counties to approve affordable housing in areas zoned residential only.

Some experts say they expect litigation and increased public furor as mammoth Live Local applications proliferate across Miami-Dade.

In Miami’s West Little River neighborhood, for instance, a developer has submitted plans under Live Local to Miami-Dade County for a 3,200-unit mega-project that calls for six apartment towers ranging from 26 stories to 37 stories, plus garages totaling 4,200 parking spaces, on properties now occupied by single-story buildings.

Another massive project, submitted to the city of Miami, would bring more than 1,000 apartments and three eight-story buildings to the site of South Florida’s last Sears store, at Coral Way and Douglas Road, on the border with downtown Coral Gables.

WORRIES IN WYNWOOD

Some longtime Wynwood developers and property owners who nurtured the prize-winning special building rules are worried and irate.

Because Live Local automatically pre-empts local rules on height and density, city and county officials have no ability to scale back proposals made under its rules or even consider them in public hearings ‘ which are barred by the law if projects otherwise meet local zoning requirements.

“With all the work we put in over 12 years to craft this zoning overlay, then this comes in and allows just craziness to occur,” said David Lombardi, a longtime Wynwood developer who built the first new housing in the neighborhood, Wynwood Lofts, in 2003. “I do find it offensive. It’s going to really ruin the scale and feel of the neighborhood that we have tried so hard to maintain. It now has a nice character and scale, and then you plunk down a 48-story building in the middle of it, it’s going to feel sh—y.”

Ironically, the Bazbaz tower plan comes as truly affordable housing is coming to Wynwood as part of the plan that Lombardi and other local developers shepherded to city approval over a period of two years. The district, known as NRD-1, generates fees from developers who build in Wynwood for a housing fund that has raised millions of dollars to subsidize development of affordable apartments in the area.

Two projects that will include housing for low- and very-low-income residents, including transitional housing for the formerly homeless, are now under development.

The first, the 12-story, art-filled Wynwood Works, co-developed by Magellan Housing and the Miami Heat’s Udonis Haslem, is under construction across the street from the site of the Bazbaz property.

Wynwood Works comprises 120 income-restricted apartments, 24 of which will be set aside for 50 years for people making half the county median household income and below. According to the state, that would mean 2024 rents for a studio ranging from $596 to $993. The rest of the units will be workforce housing, legally defined by the county as households making 60-140% of median county income.

The second, View 29, will consist of 116 apartments with rents ranging from affordable to workforce housing at Northwest Second Avenue and 29th Street. Developed by New Urban Development, an arm of the Urban League of Greater Miami, the project is in permitting review.

Because the fees for the fund are generated by allowing developers to build up to the NRD-1 height and density caps, backers fear Live Local will gut the district’s affordable-housing program because they won’t need it to build bigger.

In addition, Live Local exempts the portion of a project that’s “affordable” from paying local property taxes, another challenge for local officials who must contend with their impact on services and infrastructure.

DEVELOPER DEFENDS TOWER PLAN

Sonny Bazbaz, president of Bazbaz Development, said critics’ concerns about the impact of his proposed tower are misplaced.

The firm, then based in New York before moving operations to Miami, leased the Wynwood property, which occupies half a city block, in 2016, then bought it for $12 million in 2022. Before Live Local was approved, Bazbaz had submitted plans for a 12-story, mixed-use building with 326 residential units on the vacant property.

But Live Local changed their financial calculations, Bazbaz said.

The lot, at 65,000 square feet, was big enough to accommodate a much larger project, and Live Local made a tower ‘ far more expensive to build ‘ economically feasible, even with the more affordable units.

Helping the economics is the fact that by dividing the land cost over a bigger number of apartments, the developer’s profits increase, helping essentially subsidize lower rents for income-restricted units. High land prices in Miami are a key driver of housing costs.

“We clearly realized it was a great opportunity,” Bazbaz said in an interview with the Miami Herald. “I think the legislation is beautifully crafted. In Wynwood, it makes total sense. Miami right now is the most exciting city in the U.S. Everyone’s interested in investing in Miami, and Wynwood is the coolest neighborhood in Miami.”

The family-run firm has a portfolio of projects in New York City, but none approaching the size of the proposed Wynwood tower, and none with affordable or workforce housing. In what many developers say is a challenging financing environment as lenders get stingy and interest rates remain high, Bazbaz nonetheless thinks he and his partners can pull off the tower project.

Many details are yet to come, including precise rent levels and whether the firm will apply for subsidies available under Live Local.

But Bazbaz, who worked as an intern for Tony Goldman, the late father of Wynwood’s revival, said the project’s height won’t mean it’s out of place in the neighborhood. That’s because its design embraces the neighborhood’s aesthetic, he said. The walls of the garage above ground level will be covered on all four sides with a masonry graffiti relief that will be done by artist Bisco Smith and recall the scrawl of a street tag, though on a monumental scale.

“I understand the concerns with the difference in scale. We will figure out a way to make it work,” Bazbaz said. “I’m not an urban planner. But I know there are neighborhoods in New York that have tall buildings next to short ones. How we reconcile these two things is where magic will happen.

“I’ve seen the evolution of Wynwood. I can tell you our building has the DNA of Wynwood in it.”

DESIGN BOARD REJECTED PLAN

One important body vehemently disagrees.

On June 4, the city board set up under the NRD-1 rules to review the design and required artistic elements of new buildings and renovations in Wynwood unanimously recommended that the city planning and zoning department reject the project’s design.

Members of the Wynwood Design Review Committee acknowledged they have no ability under the Live Local pre-emption rules to address the project’s size and scope even though most felt it was wildly out of scale with the neighborhood.

But the massive parking pedestal does fall within the board’s authority, and board members said its design at ground level by the Miami firm Arquitectonica ‘ a 230-foot length of uninterrupted glass walls on all three street fronts ‘ is monolithic, the antithesis of the Wynwood aesthetic and NRD-1 rules that call for masonry walls and art.

“It’s just a big block. It’s just going to be overwhelming,” said the review board’s chairman, Marc Coleman, an architect.

Coleman and his fellow board members said they were struggling to address design issues posed by a massive parking pedestal and a tower never contemplated in the district rules that they’re supposed to enforce. Those rules call for concealed or disguised garages and sidewalk-level designs that are pedestrian-friendly and recall the graffitied, industrial look of Wynwood’s old warehouses.

Some expressed frustration they could not do more to limit the project’s scale and impact other than to recommend design tweaks to the city.

“This project in my opinion marks the end of Wynwood 2.0,” said committee member Jordan Trachtenberg, an architect who has worked in Wynwood, alluding to the redevelopment produced under the NRD-1 rules. “It’s more like Edgewater West.

“This is just starting. There will be many more. North Miami Avenue will look more like Biscayne Boulevard downtown. It’s very much not in the ethos of what Wynwood was based on. Basically, we’re powerless. It’s futile for me to even talk about this.”

Added board member Shamim Ahmadzadegan: “It’s a narrow box on top of another box. We feel it’s overly simplistic. I would use the term ÔÇÿunremarkable.’ That’s not a term I would connect to Wynwood. Is there an opportunity for more?”

Some board members also took aim at the project’s supposedly affordable units.

“The Live Local act really does not actually deal with workforce housing. It’s a complete ruse,” said architect/designer Amanda Hertzler. “A $100,000 income being considered as affordable housing is ridiculous.”

PROJECT HAS A KEY SUPPORTER

The Bazbaz proposal does have one vocal Wynwood defender in David Polinsky, a developer who was a key backer of the NRD-1 rules and the first to put up a mixed-use building in the neighborhood.

Polinsky, the only member of the public to speak to the committee about the tower, said it has several positive elements, including apartments potentially affordable to young professionals who work in the neighborhood and more people to provide street life and support local businesses.

“The shocking part for many people is just the idea of a tall building in Wynwood. And they’re right,” Polinsky said in an interview. “But more-affordable apartments is a good thing. The people who work in Wynwood can’t afford to live in Wynwood, and that’s a big problem. To put more bodies on the street, for my view, it’s a fulfillment of the goals of the NRD.”

He also said he believes the project’s impact will be limited. Polinksy noted it’s located on the so-far quieter southern end of the neighborhood, and there’s a city trolley stop directly in front, reducing the need for car trips for residents. There’s also a promised commuter rail station at the FEC tracks a short walk away.

Moreover, remaining undeveloped properties in Wynwood are small and owned by many different developers, making them unlikely sites for towers as large as the Bazbaz project.

“I only expect Live Local on big sites,” he said. “Because of fractured ownership, you’re not going to get one tower next to another.”

Even with a tower above, he added, it’s possible for a large garage podium design to embrace the Wynwood ethic at sidewalk level, where people notice it.

“You won’t know there is a tower there unless you’re flying a drone,” Polinsky said.

The biggest problem with Live Local, said Mullerat, the author of the NRD-1 plan, is that it’s based on a fundamental misapprehension ‘ that density requires height. The Live Local law allows developers to build as tall as the highest construction permitted within a radius of one mile.

In doing so, it utterly disregards surrounding characteristics and conditions. Some of the world’s densest neighborhoods and cities, such as Barcelona, have mostly low- and mid-rise buildings, Mullerat noted.

In planning the NRD-1, developers agreed to limit overall allowed development capacity, even as the plan increased zoning density from 35 units an acre to 150. That created a balanced scale that allows the neighborhood to thrive and property values to increase, for instance, Mullerat noted.

Live Local, by contrast, allows up to 1,000 units per acre, a number that is virtually impossible to reach in real conditions, Mullerat said. The law, he said, is “obviously a grab for density” for developers with no basis in planning.

The Live Local goal of expanding the supply of housing, even if it’s not strictly affordable, is laudable, Mullerat and other critics say. The problem lies in its indiscriminate approach, he said. “It’s a blunt instrument,” he said.

“We need more of a scalpel. In Wynwood, the developers imposed on themselves the design review committee and other things they didn’t have to. The idea was to keep as much density as possible within a human scale. And they did so because they understood the value of the district would increase for them if there were certain controls in place.

“I fear the Live Local Act has been written by attorneys and there is no understanding of planning, character or place. ”