CLIENT NEWS: Massive Miami makeover? 5,000 affordable apartments proposed for aging industrial area

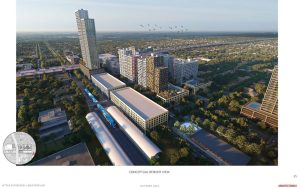

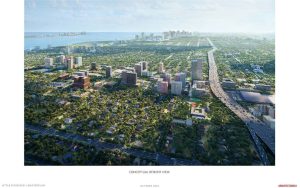

February 13, 2024A gargantuan redevelopment proposal by a prominent Miami developer would dramatically reshape a nearly mile-long stretch of the city’s Little River and Little Haiti neighborhoods, bringing big-box stores, a new Tri-Rail station and nearly 5,000 affordable and workforce apartments to a hardscrabble area in dire need of new housing and jobs but leery of gentrification.

Unlike much of the redevelopment now enveloping Miami, which is focused on high-income people and luxury apartments, the plan spearheaded by Coconut Grove-based developer Swerdlow Group is aimed squarely at low-income and middle-class Miamians who are now finding it increasingly unaffordable to live in the city, especially in the urban core.

Swerdlow submitted the plan to Miami-Dade County in response to a request for proposals to rebuild and expand four of its public housing projects in the neighborhood. But the veteran developer’s plan goes significantly beyond that, encompassing an eye-popping 65 acres of private and public land in total. The $2.6 billion project, which requires county approval, would be mostly privately financed and take nearly 10 years to finish.

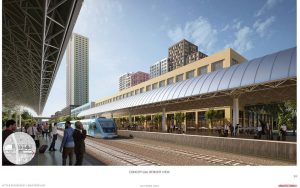

The properties, though not all contiguous, extend in a band two to five city blocks wide that runs roughly from just west of Interstate 95 to Northeast Second Avenue. The properties, now mostly industrial aside from the housing projects, straddle an active Florida East Coast Railway freight spur that the Tri-Rail commuter line uses for its new service to downtown Miami.

“As you can see, this is no small undertaking,” Swerdlow said in an interview as he described the scope of his proposal.

Swerdlow and a project partner that owns extensive property in the area, AJ Capital Partners of Nashville, were the only developers to respond to the county bid request.

AJ Capital, which bought a majority stake in a 27-acre collection of mostly industrial properties in the neighborhood in 2021 from Miami owners who had converted several into hip cafes, workplaces and shops, would redevelop its piece separately but under Swerdlow’s guidance, likely for a more upscale market.

The result, the developers say, would be a mixed-income, walkable and transit-friendly neighborhood offering residents not just apartments at a wide range of prices, but also jobs, shops and amenities, including a Home Depot and 700,000 square feet of new parks and green space.

Swerdlow said the proposal is “certainly” one of the largest redevelopment plans in Miami history, if not the largest.

David Dech, executive director of the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority, Tri-Rail’s parent, said the new station Swerdlow proposes to build as part of the redevelopment could whisk residents downtown or to the service’s main line at the Hialeah transfer station in a few minutes.

“It’s very preliminary, but from what I see it would be a fantastic place for a station,” Dech said. “The project seems well thought-out. This would be a good thing.”

The project area consists mostly of a ramshackle stretch of aging and sometimes vacant warehouse and industrial buildings, auto-body shops and empty lots, though a longstanding working-class neighborhood of single-family homes sits to its north.

LITTLE HAITI IN TRANSITION

The broad area has been known as Little Haiti since the 1980s, when Haitian refugees began moving into a neighborhood originally known as Little River. The city of Miami still officially considers the project area part of Little Haiti, long one of Miami-Dade’s poorest neighborhoods.

As the Haitian presence and population has waned, however, the Little River name has come back into use for a portion of the area, at times provoking friction with longtime Haitian residents and activists fearful of looming gentrification and accelerating displacement. Another planned major but slow-to-start redevelopment, the Magic City Innovation District, has been dogged by controversy as it aims to turn acres of land in the heart of Little Haiti into a mini-city of high rise apartments and commercial projects with no affordable housing component.

Despite its breadth, the Swerdlow proposal, submitted in November, has so far flown under the public’s radar. The advertised request by the county and Swerdlow’s extensive and detailed plan are public record, but county officials declined to comment, citing a “cone of silence” rule meant to bar lobbying while proposals are vetted. Swerdlow said county officials have yet to formally respond to his submission, but he said he believes it fully complies with the bid requirements.

Typically, if a plan submitted under a county request meets muster, officials and developers negotiate a formal agreement before consideration by the Miami-Dade Commission, a process that can take months.

Swerdlow stressed that his plan meets a key county condition — that no one living in the housing projects will be forced out as a result of redevelopment.

“It’s all middle-class stuff and affordable stuff. There is no gentrification,” Swerdlow said.

The county sought proposals under a federally sponsored program that encourages the conversion of traditional, often outdated and deteriorated public housing projects into modern communities for both low-income and middle-class residents. The program requires that existing public housing residents, who have very low incomes, be provided new apartments in the new buildings at the same low rents they were already paying, so that no one is involuntarily displaced.

The county request comprised Victory Homes, a 148-unit. low-density housing project originally built as barracks for World War II veterans that is bisected by I-95, and New Haven Gardens, an aging 82-unit project off Northeast Second Avenue at the other end of the proposed redevelopment zone, as well as two smaller projects and a county housing agency storage depot.

Swerdlow’s plan would replace and significantly expand the old projects with dense clusters of new mid-rise and high-rise apartment buildings with a total of around 1,400 units affordable to people with low and very low incomes. Existing public-housing tenants would move into new housing at the same rents and same location once construction, which would take place in phases, is completed.

RESIDENTS HAVEN’T SEEN DETAILS

A couple of public housing residents who spoke with a reporter said they were generally aware that redevelopment plans were afoot, but did not know details.

One New Haven Gardens resident of seven years, getting out of his car with his young daughter after picking her up from school, said he would welcome redevelopment of the rundown complex.

“That would be great,” Ruben, who declined to give his last name, said as he gestured to the forlorn surroundings. “They definitely need to tear all this sh– down. They don’t take care of it. You can tell. Even the Uber drivers are afraid to come in here.”

At relatively tidy if spare Victory Homes, meanwhile, where kids rode their bikes through the neighborhood streets, one eight-year resident said she did not oppose redevelopment but would likely choose to leave to avoid disruption from construction.

“It’s frustrating because we don’t know the details, but you get used to where you are,” said Kaleena, who also declined to give her last name. “The houses are in pretty good shape. I like it the way it is. Also, I don’t care for high-rises. I’d rather be on the ground.”

In addition to the affordable units, Swerdlow proposes to build some 3,500 income-restricted workforce apartments. Those would be affordable to people making no more than 120 percent of the county’s median household income, or a maximum of around $90,000. The plan classifies those apartments as rentals, but Swerdlow said he is considering marketing some as condos, with the same income limits.

Swerdlow emphasized that his group’s buildings would neither look or feel like affordable housing and would be full of amenities like gyms, gardens and swimming pools and feature high-quality design and finishes.

“These will be tremendously different from your typical affordable housing,” he said.

The public housing units would remain affordable in perpetuity, while the workforce housing rent limits would remain in place for 30 years, a typical span. AJ Capital has not yet drawn up plans for any extensive new construction.

Swerdlow also has signed an agreement to buy several properties that made up the shuttered ABC Supply company, just west of I-95, and has a letter of intent from Home Depot for a new store in its place. Other big-box stores have also expressed interest in the location and can be accommodated as part of the project with some design changes, he said.

A new, pedestrian-friendly main street of ground-floor neighborhood shops would be created along Northwest 73rd Street to connect the redeveloped Victory Homes site with the AJ Capital properties at the center of the project area.

The new development would abut the Catholic Archdiocese of Miami’s St. Mary’s Cathedral and its parochial school, an important neighborhood center. Swerdlow’s proposal includes an enthusiastic letter of support from Catholic Archbishop Thomas Wenski.

Nonprofit group Oolite Arts, meanwhile, has started construction on its new $30 million headquarters in the middle of the proposed redevelopment area.

Miami-Dade’s housing agency put its neighborhood properties up for redevelopment under a federally supported program called Rental Assistance Demonstration, or RAD.

The county has at least one other major RAD project in progress — the redevelopment of historic Liberty Square in nearby Liberty City. Developer Related Group’s affordable housing division is the midst of transforming the aging 1930s project into a mixed-income, 55-acre community with 1,900 new apartments and townhomes, or some 1,100 more units than previously existed on the site.

Though the Related project has come under under fire in a new documentary, “Razing Liberty Square,” that contends most residents at the complex ended up moving elsewhere, the redevelopment initiative, set for 2026 completion, is generally considered a success.

NEW TRI-RAIL STATION

The Little River proposal, if approved, would outstrip the Liberty Square project in size, density and scope.

Swerdlow, a South Florida veteran developer who built Dolphin Mall and launched the massive redevelopment project now known as Sole Mia in North Miami before selling out, has also developed a major project in Miami’s historically Black Overtown neighborhood that includes 578 affordable apartments for seniors. The Sawyer’s Walk development, now nearing completion, also includes Target, Ross and Aldi stores and offices for MSC Cruises.

The developer, whose partners in the Little River venture also include Alben Duffie and Stephen Garchik, said the group has already secured financing commitments for the plan’s major elements. Federal tax credits would help finance the affordable housing pieces. The plan would also require creation of a special taxing district that would use property taxes generated by the new construction to pay for installation of modern infrastructure, such as water and sewer lines, new streets and sidewalks as well as the proposed Tri-Rail station.

Dech, the Tri-Rail director, said the rail spur’s owner, FECR, would also have to approve the station plan.

The station, which would be a mid-point stop in the service’s new shuttle trains between Hialeah’s Market Station and the downtown Miami Central Station, is a linchpin of the overall plan.

The station would be critical to getting the kind of height and density the development calls for. Under special county rules governing development around transit stations, the county can override local zoning to allow significant increases in height and density over what the city’s Miami21 zoning code would permit.

If the proposal is approved, build out of the full master plan, drawn up by the Miami architectural and planning firms Arquitectonica and PlusUrbia, would take about eight years, Swerldlow said.